Human Progress: A Review

Bleep bloop goes the impressive looking machine in the background. Judging from the graphical user interface, it is doing some kind of complex statistical calculation. One that the computer boffins in the room can barely interpret, let alone understand. As the letters and numbers cascade across the screen, one person asks themself, how did the arc of history bend towards this? More importantly, is 11:30am too early for lunch?

For a minute, they think of the days when working from home meant lunch was whenever you had a spare moment between calls. "Ahh", they sigh. Simpler times. When the most pressing news of the day was which background Debbie had chosen. Unrelentingly, the march of human progress continued, consuming all the data and information that lay in its path, until there was nothing left but fields of computers and the infinitesimal interactions of quantum processing units.

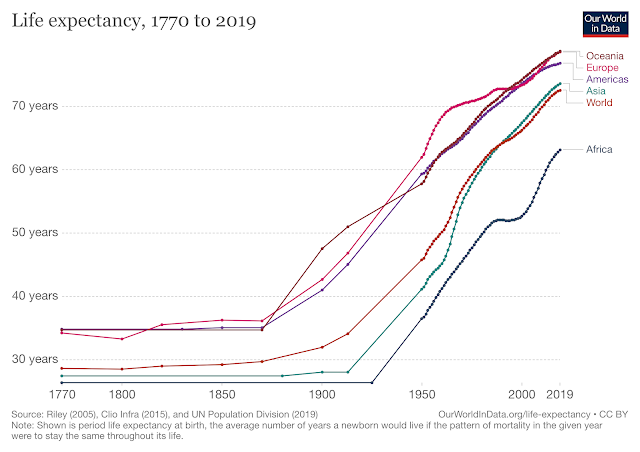

In only two centuries, we have witnessed an unprecedented rise in life expectancy. Starting in the 19th century, the world embarked on 'the Great Escape', a term coined by economist Angus Deaton for the release of humanity from its patrimony of poverty, disease and early death. However, extending human lifespan has increased the burden of diseases of ageing due to a growing period of life spent in poor health.

Ageing is defined as a decline in bodily functions and increased vulnerability to death. Therefore, in order to sustain longer lives while reducing these periods of poor health, we must develop a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of ageing. The emerging picture from genetic studies lends support to the hypothesis that ageing is driven by an imbalance in the damage and repair processes of the body. Furthermore, environmental factors such as smoking and diet interact with genes and influence the rate of unrepaired damage accumulation. As this damage accumulates, the risk of malfunctioning at the cellular level increases, which sooner or later causes age-related diseases like heart disease.

Today, heart disease is the most common cause of death in the industrialised world. It is associated with a build-up of plaque inside the arteries, consisting primarily of white blood cells and fat, which eventually reduce blood flow to the heart, the brain and other parts of the body. Analyses of previously published data show that genes associated with coronary artery disease and stroke also correlate negatively with parental longevity, suggesting shared genetic mechanisms.

As we age, our cells shut down, stop dividing and begin to secrete molecules that signal to the immune system to get rid of them before they cause damage. Currently, evidence is mounting for the role that this process plays in promoting heart disease, as it triggers inflammation, which contributes to the accumulation of arterial plaques by recruiting more white blood cells. Taken together, these findings lead us to suggest a framework for studying ageing that emphasises the interplay between genes and environment, damage and repair processes, and also inflammation (or 'inflammaging' if you enjoy unnecessary portmanteaus).

In an attempt to comprehend the complexity of biological systems in the context of disease, researchers have also begun looking at large multi-dimensional datasets and incorporating "exciting" statistical methods. For example, it is now common practice for biologists to discover genes that may cause disease in large groups of people, which can be analysed in the tissues of healthy and diseased individuals to identify drug targets.

Equally, though much more terrifyingly, recent advances in machine learning have enabled the development of AI systems that outperform us in many tasks, such as playing Atari, Go, chess, shogi and protein folding predictions, and have started empowering (and maybe one day overpowering) scientists and physicians with tools to better diagnose, prevent and treat disease. For example, deep neural networks trained on longitudinal data from healthy individuals and patients could help us predict ageing and age-related diseases.

Inevitably, the future will come to shake us from our beds, kicking the door down with its funky light-up cyborg boots and shout vague proclamations of 'solutions' to 'problems' and 'apps' for 'hair loss'. It will say with unerring accuracy what our political and sexual orientations are just by looking at us.

As we sleepwalk into this waking dream/nightmare (though more likely an amalgam of the two), let it be known that progress cannot be an uninterrupted line disappearing into the sky. We are on the cusp of a revolution in healthcare, which seeks to extend human life and reduce human suffering by using AI to better mitigate the effects of biological damage. Yet, we must acknowledge the shortcomings of our knowledge, and these approaches, and ensure that we can successfully wield these new tools while creating a desirable future for everyone.

References in text

Notable sources:

Comments

Post a Comment